Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is the only book-length philosophical work published by the Austrian philosopher during his lifetime. It was an ambitious project, to identify the relationship between language and reality and to define the limits of science concluding: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Wittgenstein wrote the Tractatus while he was a soldier and prisoner of war during World War I.

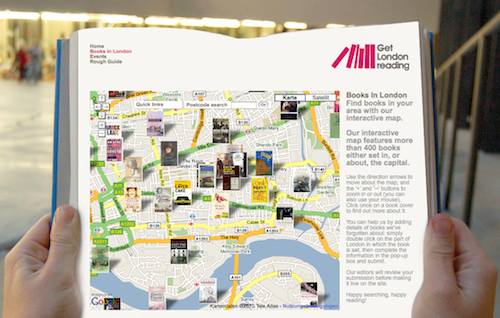

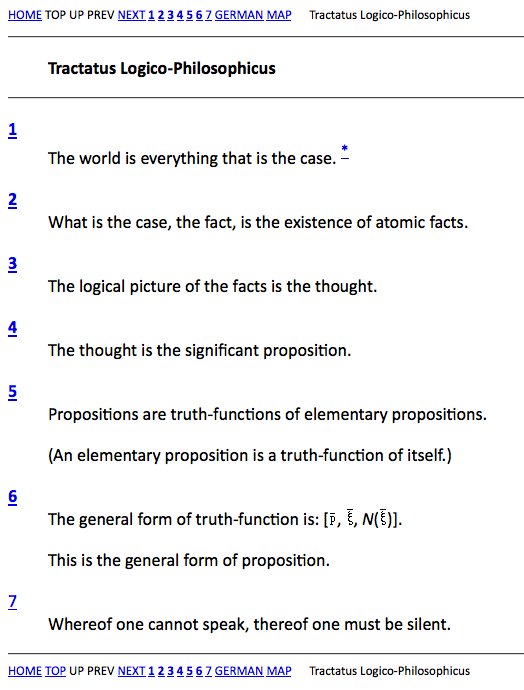

Some years ago, Jonathan Laventhol created a hypertext version of the bilingual edition of the Tractatus as a private study aid. According to him, the reader will have to make up his own mind about whether such a tool helps or hinders the appreciation of the book.

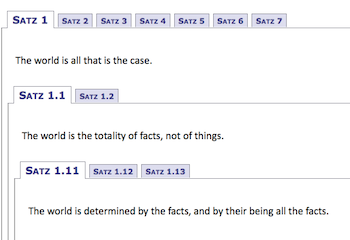

Michele Pasin, a researcher in Humanities Computing at King’s College, London, created another visualization of the Tractatus, wich tries to give the text a novel visual representation using HTML and tabs. This is part of the PhiloSURFical project Pasin developed during his PhD studies at the Knowledge Media Institute.

Althought the full text is online for free (www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5740), maybe the best way to understand the text is still the book.

Well, you could also do what Bryan Magee did and ask someone like John Searle to explain a little bit further.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qrmPq8pzG9Q

Finally, I am really not sure if Wittgenstein would have preferred hypertext to notebooks and papers. But I am convinced that different ways of exploring a text can enable the understanding.