Did you ever wonder which of your favorite literary characters lived in the same street or were actually neighbors? Now you can find it out.

Visit the Literary Map of Manhattan to see where some 100 imaginary New Yorkers “lived, worked, played, drank, walked and looked at ducks.” In my opinion this is the best combination of maps and literature so far.

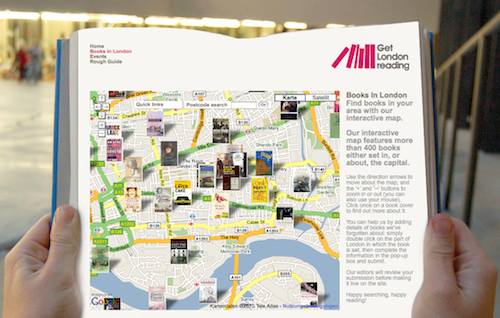

Across the Atlantic you can find a similar project called Books in London marking the location of more than 400 books either set in, or about, London.

The creators of Books in London also provide a free iPhone app of their literary map.

Still another way to explore maps and literature is Gutenkarte. The so called “geographic text browser” is intended to help readers explore the spatial component of classic works of literature. Gutenkarte downloads public domain texts from Project Gutenberg, and stores all the geographic locations it can find locations in a database, along with citations into the text itself.

You can also browse historical literary maps at the Library of Congress. This collection of maps was part of an exhibition entitled “Language of the Land“, a breathtaking journey through the literary heritage of the US.

Augmented reality is reality. And I am eager to see what is coming next.