“The children now love luxury; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, cross their legs, and tyrannize their teachers.” This famous misquotation of ancient Greek philosopher Socrates became popular in the 1960s, when it was used by the Mayor of Amsterdam and reported by The New York Times, on April 3, 1966.

Nowadays, parents and teachers once again are concerned about the bad manners or the social well-being of their kids.

Americans between the ages of 8 and 18 spend on average of 7 hours and 38 minutes a day using some sort of electronic device, from smartphones to MP3 players to computers, The Kayser Family Foundation reported earlier this year. You can go to any campus or school, and you will probably find an immediate flipping up of phones and texting when the lesson is over. Parents are concerned about the fact that kids no longer care about language as an art and gift. And they wonder: If some of these digital natives have more than 500 “friends” on social networks like Facebook, do we have to be concerned about the future?

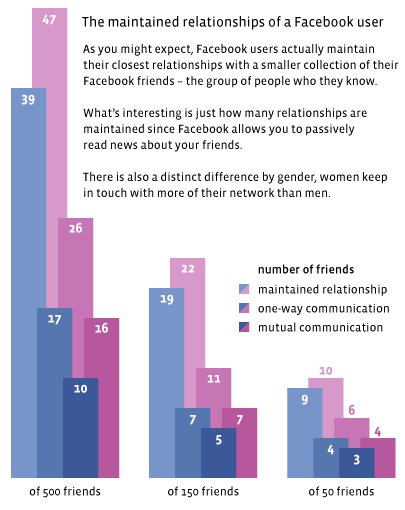

We do, certainly. But we should look a little bit closer first. As The Economist reported in an article entitled “Primates on Facebook” last year, even people with very many Facebook friends, mutually communicate only with some happy few. 10 to 16 people, according to a study of the Facebook Data Team, taking into account gender differences. The average user on Facebook has “only” 120 confirmed friend connections and mutually communicates with 3 to 7 people. This looks quite similar to the good old concept of friendship.

And even if Facebook seems to devaluate the term “friend”, and although parents might be impressed or scared of the social multitasking skills of their children, digital natives seem to be able to build up and maintain friendships in their social networks. As the Economist put it: “The neocortex is the limit.”

It was Robin Dunbar, an anthropologist from Oxford, who extrapolated from the brain sizes and social networks of apes and suggested that the size of the human brain allows stable networks of about 148. Many institutions, from neolithic villages to the maniples of the Roman army, seem to be organized around this Dunbar number. And even digital natives in their new habitat of social networks do not exceed those limits.

Until recently concerns about the use of technology have been focused on the implications for kids’ intellectual development. Now, it is taken into account how technology is affecting social relationships and friendship. This brings the worry about the social repercussions of technology from the darker side of online interactions, like cyber-bullying or texting sexually explicit messages, to the light.

In my opinion, most of the concerns of the elder generation result from something Remo Largo, swiss MD and early childhood specialist would call “misfit” between Kids’ behavior and their environment. Then education would be about rearranging learning and living to better match the children’s individual needs. That means new approaches to digital literacy to address a second digital divide. But it is also about being interested in the kids’ needs and their new virtual habitat. Better education will help them to find the balance between broadcasting and privacy, networking and friendship, multitasking and concentration, lightweight conversation and personal reflection, online networks, and real life.

This southpark episode is a very good starting point: