Take 10 men and 1 woman to think about American Education in 2030. That is what Standford’s Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, a public policy think tank, has done. The result is an ebook and a website with the author’s video comments: www.americaneducation2030.org.

First, one could argue that the group of authors isn’t the best example for gender equality. Second, the essays aren’t covering a wide range of educational issues as I expected beforehand just reading the title. The articles are clustered into Curriculum and Instruction (five), Standards and Testing (two), Governance and Finance (four), and Privatization and Choice (two), with a lot of overlapping territory, e.g., technology or national standards and testing. The best read is probably the conclusion by Chester Finn, a recapitulation of what actually changed in American education from 1990 to 2010, as a form of evidence of what is possible within 20 years.

Most of the essays are written in past tense travelling to 2030 and looking back. This Back-to-the-Future-Part-2 approach is quite entertaining and a good read.

Some authors cite Washington Irving’s Rip van Winkle and a cliché in American education: “Had Rip awakened in a classroom 20 years later, he would have noticed no changes at all.” Hopefully this won’t be true for American education in 2030. And most of the authors are convinced that change will happen. However, I would not agree with Paul E. Peterson’s top-down suggestion that “changes will move from the college level downward through high school into middle school.” In my opinion, the only starting point is “the best part of the twentieth-century school” (Peterson), the elementary school. Otherwise it would lead to a future, that President Obama described recently: “Information becomes a distraction, a diversion, rather than a tool of empowerment.”

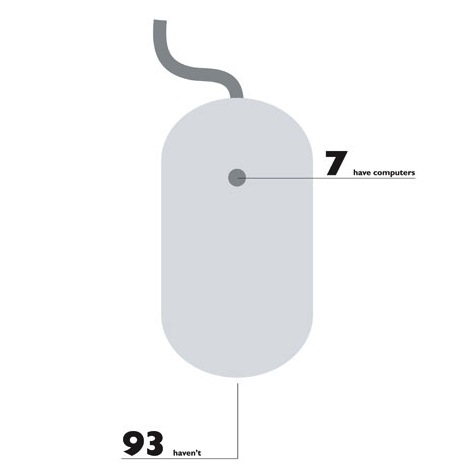

Many authors stress the benefits of computer access, new teaching materials and computer adaptive testing. In my opinion, one has to be very careful to get the use of technology in education right. Everything depends on the people teaching and learning, and how they use technology. In “American Education in 2030” I missed that perspective. Nevertheless it is a good starting point to discuss a more responsive, efficient and effective education system than we have today.

For further reading and downloading American Education in 2030 (2010), edited by Chester E. Finn Jr., visit: www.americaneducation2030.org