Leonardo da Vinci is famous for having written most of his personal notes in mirror.

There are two popular theories on why he did this. Either da Vinci was left-handed, causing the ink to smudge easily if he wrote in standard writing. Or he wanted to protect his ideas from theft or hide them from the Roman Catholic Church with whom his research practices sometimes collided. However, the latter idea is highly unlikely. Even at da Vinci’s time, the text in question could be easily read “backwards” either directly or through its reflection in a mirror. The true purpose of this practice thus remains unknown.

Which tool would he use today? It would probably be fliptext. Although it is not exactly mirror writing, it transforms the text in a similar way, using symmetry and similarities of different letters. For example s, x, z and o are rotationally symmetrical, while pairs such as b/q, d/p and n/u are rotations of each other. The rest of the letters are encoded into the Unicode International Phonetic Alphabet, creating a full set of upside-down lowercase letters.

I am quite impressed each time I try it, that it’s possible to read the transformed text, even without a mirror, or even without turning your screen upside down.

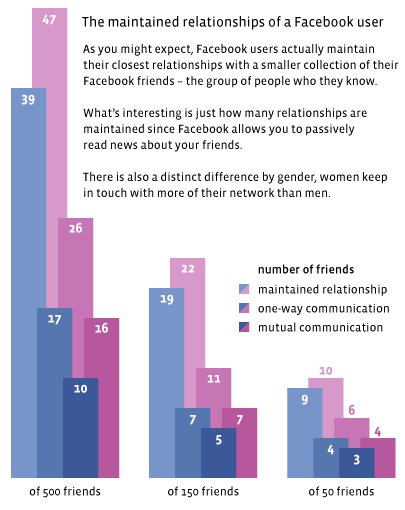

You can use fliptext to write upside down on Facebook, Twitter, Myspace or your Blog or even typing Emails, Presentations or Documents. It should work in all modern browsers and applications because it is Unicode.

Try it out!

?u?op ?p?sdn u????s ?no? bu?u?n? ?no???? u??? ?o ‘?o???? ? ?no???? u??? ‘?x?? p???o?su??? ??? p??? o? ??q?ssod s,?? ???? ‘?? ??? ? ???? ???? p?ss??d?? ???nb ?? ?

?s?????? ?s?????o? u?op-?p?sdn ?o ??s ??n? ? bu?????? ‘??q??d?? ????uo?d ??uo???u???u? ?po??un ??? o?u? p?po?u? ??? s?????? ??? ?o ?s?? ??? ?????o ???? ?o suo????o? ??? n/u pu? d/p ‘b/q s? ??ns s???d ????? ‘??????????s ????uo????o? ??? o pu? z ‘x ‘s ??d??x? ?o? ?s?????? ?u??????p ?o s??????????s pu? ???????s bu?sn ‘??? ??????s ? u? ?x?? ??? s??o?su??? ?? ‘bu????? ?o???? ?????x? ?ou s? ?? ?bno???? ??x??d??? ?q ??q?qo?d p?no? ?? ¿??po? ?sn ?? p?no? ?oo? ?????

?u?ou?un su????? sn?? ???????d s??? ?o ?sod?nd ?n?? ??? ??o???? ? u? uo???????? s?? ?bno??? ?o ???????p ?????? “sp??????q” p??? ???s?? ?q p?no? uo??s?nb u? ?x?? ??? ‘???? s,??u?? ?p ?? u??? ???????un ???b?? s? ??p? ?????? ??? ‘?????o? ?p?p???o? s??????os s???????d ?????s?? s?? ?o?? ???? ???n?? ???o???? u??o? ??? ?o?? ???? ?p?? ?o ????? ?o?? s??p? s?? ????o?d o? p??u?? ?? ?o ?bu????? p??pu??s u? ??o?? ?? ?? ???s?? ?bpn?s o? ?u? ??? bu?sn?? ‘p?pu??-???? s?? ??u?? ?p ?????? ?s??? p?p ?? ??? uo s???o??? ???ndod o?? ??? ?????

??o???? u? s??ou ??uos??d s?? ?o ?so? u?????? bu???? ?o? sno??? s? ??u?? ?p op??uo??